A Conversation with Rubén Polendo & Darrel Alejandro Holnes

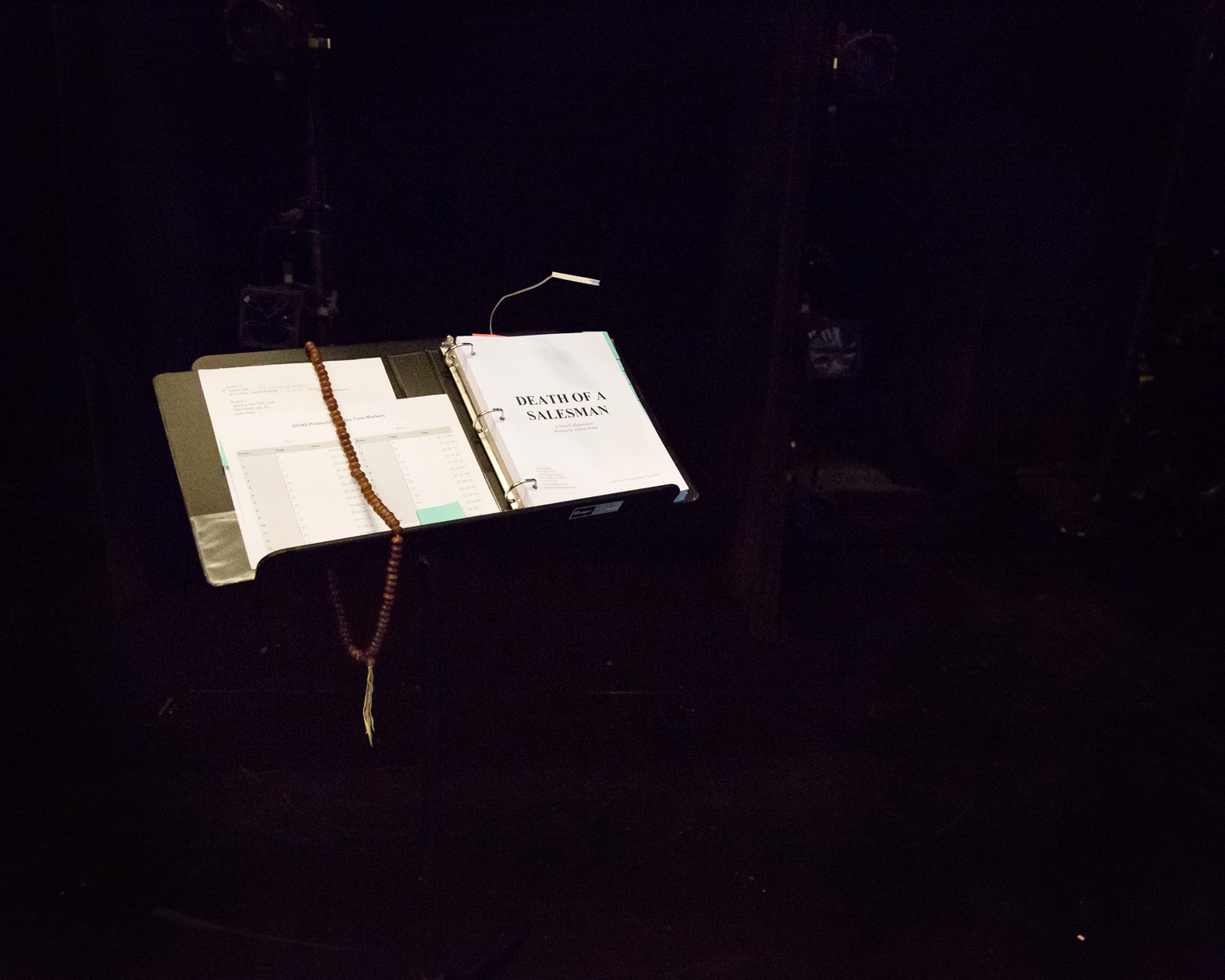

DAH: Can you talk about the theatrical approach to Death of a Salesman, and how you’re using the theatrical elements to answer the question of “What happens when you’re written out of the American Dream”?

RP: This goes back to that initial instinct. We as a company not only make work together, but we train together as well. One of the big goals is really to lean in and trust the artistic instinct, and to know that following that instinct will actually reveal the reason for that instinct. Often in making theatrical work, the artists have an instinct, and immediately that instinct is interrogated. So as an artist, you see the color blue, and someone says why is that? Why is that in the script? And you think, I don’t know! That was an instinct! We as a company actually feel that the rationale for all of our instincts we usually don’t see or truly understand until the work is complete because you’re being impacted by the text and your own ideas in the moment.

The instinct for me as a director became to manifest these four central characters and to really place them in a complete austere aloneness. That already had a kind of aesthetic implication which sort of implied an incredibly bare space, dry and absent of humanity. Once we did the pre-recorded voices, once that started, my instinct was to follow that and make [the supporting characters] these objects. There was also obviously a gravitation towards the time period so they became these objects of the time and they really became about manifesting the metaphorical language one uses for people. So if someone says, “that young man is so bright,” it literally manifests as a bright light that no one can even look at because it’s so bright. It was about taking the poetics of everyday language and manifesting them on stage. There’s something about that clarity that is so fantastic and exciting.

The equation that is then created is this world that has somehow stopped paying attention to the changes happening, but in fact, is just very blindly becoming another object or cog or piece in the machinery. We use this emotional focus on the family that is actually trying to stay human and ask questions and explore. The result is this very asphyxiating experience with, say Willy, as he’s sitting surrounded by these other characters that have now become objects, and truly saying, help me, please help me. And the objects are completely inhuman, and out of the recording comes, It’ll get better tomorrow! Willy, what’s going on next Thursday? And they keep ignoring him. It’s really frustrating to watch, because the objects just go about themselves, and it really becomes this cautionary tale of what happens when you ignore.

full conversation